Bislama is an English-based creole language and the primary lingua franca of Vanuatu, spoken by over 95% of the population. Originating from the 19th-century plantation era, it combines English vocabulary with distinct Melanesian grammatical structures to bridge the gap between Vanuatu’s 113 indigenous languages, serving as a vital tool for national identity and communication.

What is Bislama? Defining the Language

To truly understand the culture of Vanuatu, one must first ask: what is Bislama? It is far more than a mere dialect or “broken English.” Bislama is a fully developed creole language that serves as the heartbeat of the archipelago. It is one of the three official languages of the Republic of Vanuatu, standing alongside English and French, but it holds a unique position as the sole national language.

Vanuatu is widely recognized as having the highest linguistic density in the world. With a population of roughly 300,000 people spread across 83 islands, there are approximately 113 distinct vernacular languages spoken. Without a unifying tongue, communication between villages—let alone islands—would be nearly impossible. Bislama fills this void. While most Ni-Vanuatu (citizens of Vanuatu) speak their own local vernacular at home, Bislama is the language of commerce, politics, and social interaction in urban centers like Port Vila and Luganville.

Linguistically, Bislama is classified as an English-lexifier creole. This means that the vast majority of its vocabulary (lexicon) is derived from English. However, the grammar and syntax are distinctly Oceanic, mirroring the structures found in the indigenous Melanesian languages. It shares a family tree with Tok Pisin (spoken in Papua New Guinea) and Pijin (spoken in the Solomon Islands), collectively forming the Melanesian Pidgin family.

The Origins: From Sea Cucumbers to National Identity

The history of Bislama is inextricably linked to the colonial history of the Pacific and the complex dynamics of trade and labor. The etymology of the word “Bislama” itself offers a clue to its origins. It derives from the French word bêche-de-mer (sea cucumber). In the early to mid-19th century, traders scoured the Pacific for sea cucumbers, a delicacy in Chinese markets. The contact language that developed between these traders and the islanders was initially termed “Beach-la-Mar.”

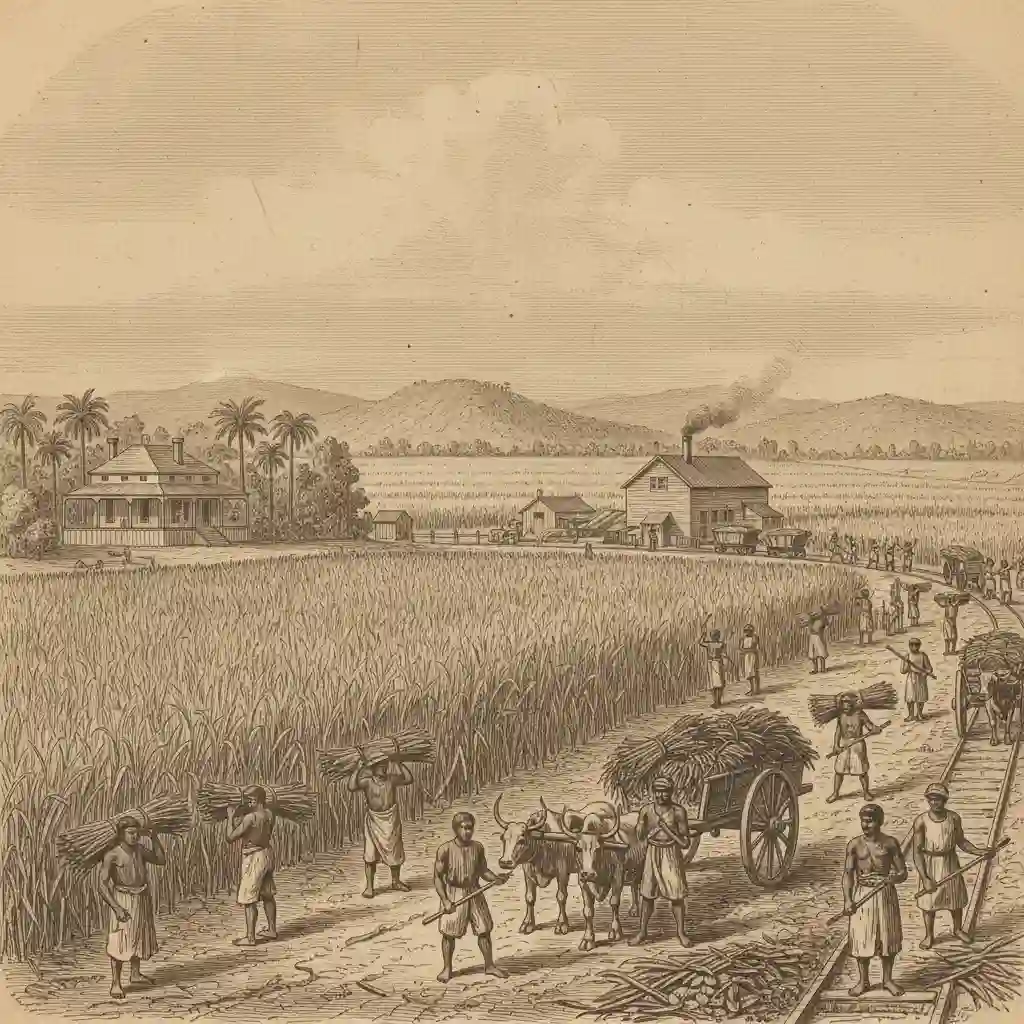

The Blackbirding Era

The language solidified and expanded during the “blackbirding” era of the 1870s and 1880s. During this dark period, thousands of Ni-Vanuatu men were recruited—often through coercion or kidnapping—to work on sugar plantations in Queensland (Australia) and Fiji. On these plantations, laborers from dozens of different islands, who shared no common language, were thrown together. To communicate with overseers and each other, they developed a stable pidgin based on English vocabulary.

When the labor trade ended and these workers returned to the New Hebrides (now Vanuatu) at the turn of the 20th century, they brought this pidgin language with them. It became a prestigious marker of travel and experience. Over the subsequent decades, it spread throughout the archipelago, evolving from a rudimentary pidgin (a second language used only for trade) into a creole (a primary language learned by children).

Vocabulary: A Linguistic Melting Pot

While Bislama is often described as having an English lexicon, a closer inspection reveals a fascinating tapestry of linguistic influences that mirror Vanuatu’s colonial history. Approximately 90% to 95% of the words are of English origin, but their usage and pronunciation have been adapted to fit Melanesian phonology.

French Influence

Due to the Anglo-French Condominium (1906–1980), where Vanuatu was jointly governed by Britain and France, French vocabulary has seeped into Bislama. This is particularly noticeable in culinary terms, administrative words, and interjections. Examples include:

- Bonane (from bonne année) – Happy New Year.

- Pam (from pomme) – Apple.

- Kalsong (from caleçon) – Shorts or underwear.

Indigenous Flora and Fauna

English lacked the specific terminology to describe the rich biodiversity of the Melanesian environment. Consequently, Bislama retains many words from local vernacular languages to describe native trees, animals, and cultural concepts. Words like nakamal (meeting house) and kava (the traditional drink) are universal across the islands.

Evolution and Modernization

Bislama is a dynamic, living language. In the digital age, it is rapidly adopting new terminology. However, rather than simply borrowing the English word directly, Bislama often uses descriptive compounding. For example, a computer might traditionally be described, but increasingly, English loanwords are being phoneticized (e.g., komputa).

Bislama Grammar: Simplified Yet Sophisticated

Newcomers often make the mistake of thinking Bislama is “simple” because it lacks the complex conjugations of European languages. There is no gender, and verbs do not change form based on the subject (I go, she goes, we go). However, Bislama possesses a highly structured grammar with nuances that English lacks, particularly in its pronoun system.

The Complexity of Pronouns

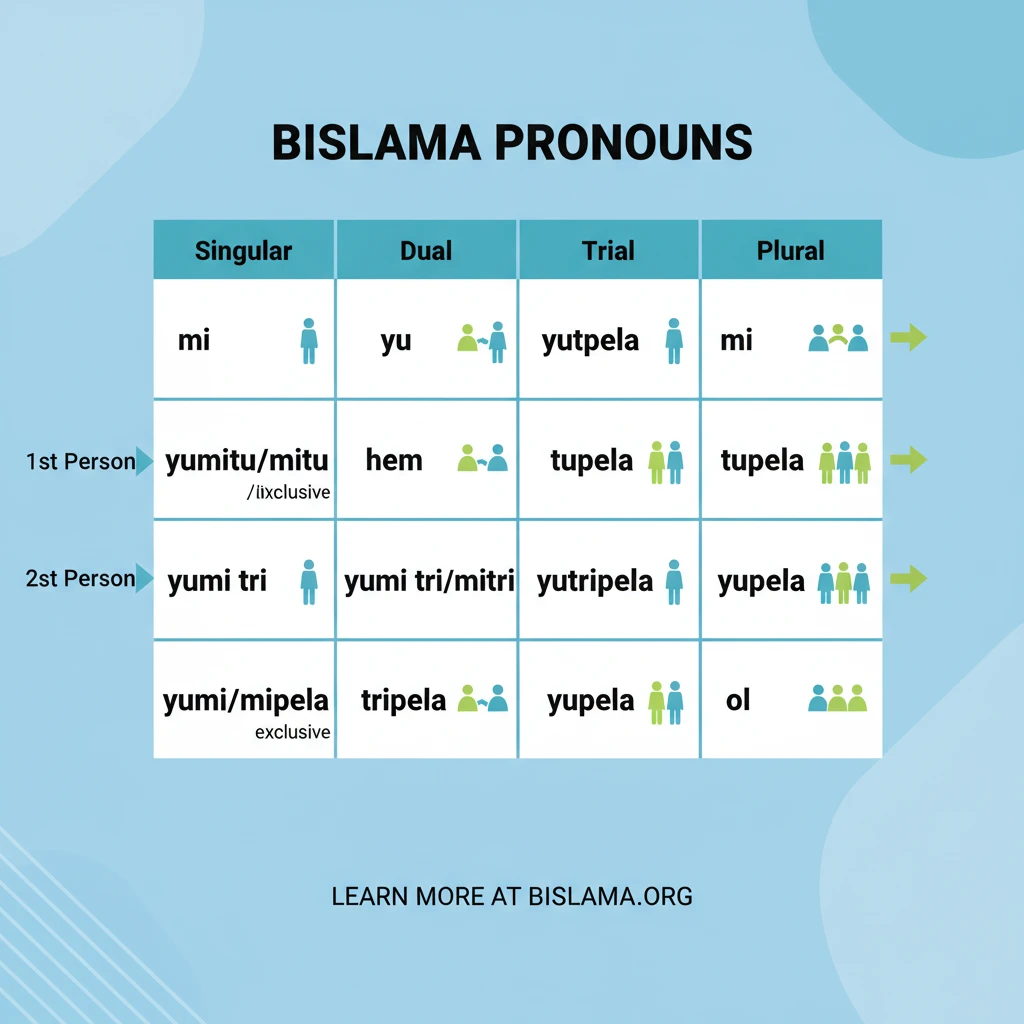

English has a relatively limited pronoun set. Bislama, following Melanesian patterns, is much more precise. It distinguishes between singular, dual (two people), trial (three people), and plural (four or more). Furthermore, it distinguishes between the inclusive and exclusive “we.”

- Yumi (We inclusive): You and I (and perhaps others) are included.

- Mifala (We exclusive): Me and others, but not you.

Using the wrong form of “we” can completely alter the meaning of a sentence. If you say “Mifala i go long beach” to a friend, you are telling them that you and your group are going to the beach, but your friend is not invited. If you say “Yumi go long beach,” you are inviting them along.

The Predicate Marker “i”

One of the most critical grammatical rules in Bislama is the use of the predicate marker “i” (pronounced ‘ee’). This particle separates the subject from the verb in the third person. It is not a pronoun; it is a grammatical marker.

- Hem i kakae. (He/She is eating.)

- Man ia i wok. (That man is working.)

Omitting the “i” is the most common marker of a non-native speaker.

Transitive vs. Intransitive Verbs

Bislama verbs often carry a suffix to indicate transitivity (whether the verb has a direct object). The suffix is usually -em (derived from “him” or “them”).

- Dring (Intransitive): Mi dring. (I am drinking.)

- Dringim (Transitive): Mi dringim kava. (I am drinking kava.)

This rule is consistent and essential for clarity. A verb ending in a vowel might take -im or -um for phonetic harmony, but the function remains the same.

Why Bislama is Important to Vanuatu Identity

Bislama is the glue that holds Vanuatu together. In a nation where a village five kilometers away might speak an entirely different language, Bislama is the medium of democracy, education, and law. It is the language of the Vanuatu Parliament, and the national motto is proudly displayed on the coat of arms in Bislama: “Long God yumi stanap” (In God we stand).

Beyond utility, it is a source of pride. During the struggle for independence in the 1970s, Bislama became a symbol of Ni-Vanuatu unity against colonial powers. Today, it is the language of music (Reggae and String band), radio, and the rapidly growing local internet community.

Practical Bislama for Travelers

If you are planning a trip to Vanuatu, learning a few phrases of Bislama will earn you immense respect and warmer smiles from the locals. While English is widely spoken in tourist areas, using Bislama shows an appreciation for the culture.

- Halo – Hello.

- Olsem wanem? – How are you? (Literally: Like what?)

- Mi stap gud – I am fine. (Literally: I stop good.)

- Tangkyu tumas – Thank you very much.

- Si – Yes.

- No – No.

- Mi no save – I don’t know / I don’t understand. (Pronounced ‘sah-veh’, from French ‘savoir’).

- Hamas long hem? – How much is this?

People Also Ask

Is Bislama hard to learn for English speakers?

No, Bislama is generally considered one of the easiest languages for English speakers to learn. Since approximately 90-95% of the vocabulary is derived from English, the lexical learning curve is flat. The challenge usually lies in mastering the specific grammar rules, such as the pronoun system and the transitive suffixes, and understanding the unique pronunciation.

What is the difference between Bislama and Tok Pisin?

Bislama (Vanuatu) and Tok Pisin (Papua New Guinea) are closely related sister languages within the Melanesian Pidgin family. They share a high degree of mutual intelligibility. However, they differ in vocabulary influences; Bislama has more French loanwords due to Vanuatu’s colonial history, while Tok Pisin has more German and indigenous influences. There are also slight differences in pronunciation and grammar.

Why is it called Bislama?

The name “Bislama” is derived from the early 19th-century trade of sea cucumbers, known as “Bêche-de-mer” in French. The language that developed between traders and locals to facilitate this trade became known as “Beach-la-Mar,” which eventually evolved phonetically into “Bislama.”

Is Bislama a written language?

Yes, Bislama is a written language with a standardized orthography, although spelling can sometimes vary in informal contexts. It is used in newspapers, the Bible, social media, and official government documents. The dictionary “A New Bislama Dictionary” by Terry Crowley is considered the standard reference.

Do all people in Vanuatu speak Bislama?

While not every single individual speaks it, Bislama is the most widely spoken language in the country. It is spoken as a first or second language by over 95% of the population. It is less common among the very elderly in extremely remote villages, but for the vast majority of the population, it is the primary means of communication outside the home.

What does “Long God yumi stanap” mean?

“Long God yumi stanap” is the national motto of Vanuatu. It translates to “In God we stand” or “Before God we stand.” It reflects the strong Christian heritage of the nation and the unifying role of faith in bringing the diverse islands together under one flag.